The Events of September 1777:

From Brandywine to Valley Forge

What Did the People of Chester County Think About the Revolution?

Chester County had 13 delegates at the 100 person Pennsylvania convention to form a revolutionary government in May 1776, including Richard Thomas of West Whiteland.

Families in Chester County undoubtedly divided over both the question of independence and the “radical” government that came to power in Spring 1776, weeks before Pennsylvania voted to support the declaration drafted by Thomas Jefferson with help from Franklin. This schism would play out as war came to Chester County in late Summer, 1777.

Largely because they were pacifists, the Quakers leaders were considered closet loyalists, so the new Pennsylvania government demanded they sign oaths of loyalty to the new Revolutionary government. Some who refused were arrested and sent by wagon through Reading first to York and then south to Winchester and Augusta (Staunton) Virginia. They would be held there for eight months while Philadelphia was occupied by the British.

Amish families (also pacifists) had arrived in the Chester Valley in the 1760s and lived as far east as Tredyffrin Township. They spoke mostly German and many resisted the March 1777 Militia Act (requiring enlistment of adult males) and July 1777 acts which required “citizens” to swear allegiance to the new Pennsylvania government in order to vote or hold office. Many had migrated to America to avoid decades of war in Southern Germany and Switzerland. Again, they were viewed as a danger to the new government

Armies do not wait while commanders “ask directions.” Both sides had spy networks since the days of Paul Revere and Williams Dawes at Lexington. And there were Loyalist sympathizers in Chester County as well, willing to help suppress this infamous rebellion by leading British troops through the county during September 1777.

July 1777 - The British Changed Course

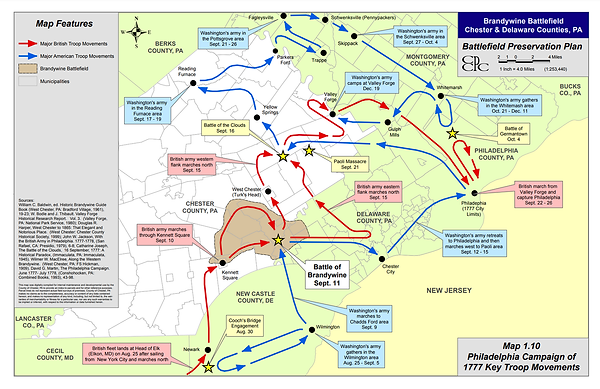

General William Howe and his naval commander brother Richard sailed with 200 ships from New York City in July 1777. Their destination was not clear but they were observed sailing past the Delaware Bay. The American army did not know their planned destination, but the British were finally seen landing in late August near Elkton, Maryland after a voyage of almost six weeks.

Despite their lengthy sea voyage, British marched east toward Wilmington where they engaged the Americans at the Cooch’s Bridge on Sept. 3, and won. The British army then marched north into Pennsylvania arriving in Kennett Square on Sept. 10. The Americans anticipated an assault on Philadelphia and marched from central New Jersey through Philadelphia and out the Baltimore Pike toward Chad's Ford across the Brandwyine Creek.

September 9-10 -

The Revolution Arrives in Chester County

"The Americans arrived at John Chad's ford across the Brandywine and sent an advance party toward the Kennett Meeting House. The core forces were aligned alone the east shore of the Creek on the high ground near the Chad house (Creek Rd), They expected a full frontal assault.

*Kennet Square was mostly an area populated with Loyalists who could aid the British concerning roads, bridges and "friendly" farms nearby.

September 11 - Battle of Brandywine

"To understand the scope of the engagement on the locality, Chester County had roughly 5,000 residents in 1777. It was visited by more than 30,000 soldiers and supporting civilians (teamsters, camp followers, domestics). The British brought with them 4,000 horses and 350 wagons. The American supply train was far smaller but it is little wonder what the impact three weeks of war in Chester County would leave. Crops were destroyed, houses pillaged and the dead and wounded often left on the field."

- Mark Ashton, Chester County: A Modern History

The British army divided with the smaller force marching directly up Baltimore Pike towards Chads Ford while 9,000 men, led by Lord Charles Cornwallis, marched a 12-mile trek through wooded areas led by local Loyalists sent by a former member of the Continental Congress: Joseph Galloway. The British were accompanied by 6,800 Hessian troops led by General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, who was tasked to attack the American center at Chadds Ford as a diversion. The attack from the British and the Hessians overwhelmed Washington's army: the battle lasted for 12 hours, and both sides were exhausted. As a result, the Continental Army retreated to Chester, PA. The British had 90 killed and 480 wounded. The Americans 300 killed and 600 wounded.

Two meetinghouses were involved in the battle:

the Kennett Meetinghouse and the Birmingham Friends Meetinghouse.

September 12-15 - Playing Chess with the British

Philadelphia was now on the line as Howe moved to capture it. In order for Washington to prevent Howe's army from taking Philadelphia, he would need to prevent them from crossing the Schuylkill River. He first camped in Darby, PA, and then took his army across the Schuylkill to East Falls. Realizing that the British could trap him between the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, Washington recrosses the Schuylkill on September 14 and heads west back into Chester County. The Americans arrived in Malvern where they camped near Malin Hall in East Whiteland Township.

Meanwhile, the British army hardly moved: General Cornwallis stayed at Aston while General Howe remained at Chadds Ford. Instead of marching straight to Philadelphia, Howe and his army marched to Turk’s Head (now West Chester). Howe directs Cornwallis to head north along a path close to the North Chester Rd. (Rte. 352 today) to engage the Americans just west of modern Malvern.. The British forces will converge near the Goshen Meeting House.

September 16 - Battle of the Clouds

While Washington led 10,000 troops west through the Great Valley, Howe's troops marched north on what are today's Phoenixville and Pottstown Pikes. After being alerted that the British were coming in their direction, Washington had Brigadier General Anthony Wayne and his troops advance toward the British to slow their advance. On the way, Wayne's troops encountered Hessian forces, and nearly captured Colonel Carl von Donop when he was separated from his own soldiers.

As the battle was beginning to fully engage that afternoon, skies were darkening, and rain began to pour. Without dry gunpowder, the armies could do little more than glare at each other; if they could see each other at all through what we now call a nor’easter. Washington withdrew his troops north from the White Horse Tavern to the spa village at Yellow Springs. The six mile march took 10 hours

September 17-19 - A Need for More Supplies

Washington needed dry ammunition and supplies after the rain destroyed them. He retreated northwest to the Reading and Warwick Furnaces.

Once re-supplied the Americans marched east towards Parker's Ford, while a small contingent under Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton and Capt. “Light Horse” Harry Lee was sent east to Valley Forge to remove or at least destroy a large cache of food, supplies and equipment. On September 18, General Knyphausen and 200 troops were sent from the British camp at Howellvillee to capture what was stored at Valley Forge. While there, they fired at Hamilton and killed his horse, but Hamilton was able to get to the other side of the Schuylkill.

September 20 - The Paoli Massacre

Washington tasked Anthony Wayne and 2,500 troops to track British activity in the area near modern day Chesterbrook. To do that, Wayne established a camp in Malvern. The British found this camp, and decided to surprise-attack the Americans on the night of September 20th, 1777. That night, 1,200 British soldiers led by General Charles Grey marched west on Swedesford Road to the American picket post and readied their weapons with bayonets. The surprise attack at night caught the Americans off-guard. Many tried to surrender only to find that the British gave no quarter to men they regarded not as enemy combatants but as traitors.

"The casualties were nearly as bad as Brandywine for the Americans and yet this was a small portion of the army. The British had four killed and seven wounded, a complete rout that drove the Americans west all the way to the White Horse Tavern. Hoping that General Wayne might have passed the evening at his home near Paoli, the British raided the house but found nothing of consequence. The defeat here was total."

- Mark Ashton, Chester County: A Modern History

December 1777-June 1778 -

Camping at Valley Forge

The British captured the city of Philadelphia on Sept. 26. Washington and his army marched, camped, and fought around the Montgomery County area, and faced many defeats from the British. In December he decided the army needed a fresh place to camp and the army marched from today's Fort Washington to the Matson's Ford (Conshohocken) and crossed the river. While at Gulph Mills Washington captured British tents, food and 45 British soldiers who stumbled near the encampment on Rebel Hill. It is here, on December 17 that Valley Forge is selected as the site for winter quarters and American troops observe a first “Thanksgiving.”

"The encampment at Valley Forge is 'legendary' to a degree somewhat beyond the facts. In a war that lasted from 1775 to 1783 there were many dark hours. They include the months before the Battle of Trenton and the Winter 1779 encampment at Morristown. Valley Forge is an oft misunderstood chapter in American history. It was not the worst winter of the war. It was a winter with frequent snows punctuated by relatively mild weather, which may help account for the high incidence of illness. There was no battle. The Valley Forge story has two themes. Endurance and resurrection. The endurance piece involves surviving a winter with little food and clothing. Disease did put the American army in a precarious place and had the British actually launched a winter attack on Valley Forge despite a high ground and well placed defenses, the game may well have been over. The principal enemies at Valley Forge were hunger and disease. The absence of food and clothing and the prevalence of camp borne diseases like typhus and smallpox prompted large scale desertions. And while the Americans survived Brandywine, the Clouds, Paoli and the attack of Germantown, these engagements had not disrupted the British; an enemy now comfortably ensconced in America’s new capital city."

Early in 1778 there is a Congressional inquiry into whether Washington should remain commander. The delegation sent from York where Congress is seated observes that Washington's central disadvantage is the absence of supplies. Meanwhile, on February 23 an eccentric but affable former European officer, Frederick vonSteuben arrives. In the next four months he will make this rag-tag army into an effective fighting force.

On June 19 the Americans will break came destined for New York and will engage the British in Monmouth, NJ.

- Mark Ashton, Chester County: A Modern History

Bibliography

Baumann, Roland M. "The Pennsylvania Revolution." US History. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://ushistory.org/pennsylvania/birth2.html.

Mark, Harrison W. "Battle of Brandywine." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified February 16, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2379/battle-of-brandywine/.

Pilligalli, Michael. "William Moore & Moore Hall." Chester County Day (blog). July 6. https://www.chestercountyday.com/articles/williammooreandmoorehall.

"The Battle of the Clouds." American Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783. Accessed March 8, 2024. https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1777/battle-of-the-clouds/.

Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution. (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2011): 357.

_JPG.jpg)